Normally when I write these posts, I imagine that I am writing to someone who reads them, and I pick different people for different topics.

But today, because I’m currently teaching a course on diversity and inclusion, that topic and those students are on my mind. So instead, I’m imagining you all together in a nice room (maybe the big room with the tall windows at the Mercantile Library) and am writing to both—readers and students.

I am especially writing to those of us whose skin tone is on the pale end of the spectrum. When we see what is happening in our country in 2020, when we see and hear—still—the cries to address the systemic racism that continues unaddressed, and especially when we talk with someone who is Black, we may be tempted to explain ourselves, to say, “I’m not a racist.”

We want to distance ourselves from those people in those old black and white images, who spat on Black school children as they walked—barely protected—between a row of police officers to enter a segregated school.

We want to separate ourselves from those young men, faces distorted with anger and hate, whose tiki torches blazed in the Charlottesville night sky.

Yes, we are different from that flagrant brand of racism, but we are not entirely different, and probably not as different as we think.

If you were raised in the United States, you have grown up in the rain of racism. It was in the books we read, the TV shows we watched, the words we overheard, the gestures we felt, and the looks we saw. We picked it up.

To say we are not racist is to stand in a rainstorm and say, “I am not wet.”

An example…

Not from thirty years ago, when I saw a Black man tending the roses of a lovely Tudor home and assumed he was the gardener rather than the homeowner. From a few weeks ago, and that bothers me more.

One morning, I was doing my standard meditation, using the app on my phone.

After the gong sounded, before I clicked over to check the weather, I noticed the little circles of avatars at the bottom of the screen, under the heading ‘meditated with you.’ I swiped up.

Scanning the faces and names, my eyes stumbled over one. He was a Black man, seated, legs folded into lotus, hands held in anjali mudra.

My stumble was a clue: This man did not fit my mental model of what people who do mediation or yoga look like.

My mental model was defective—it didn’t reflect reality.

People who look like Gwyneth Paltrow, or a yogi from India, or random middle-aged white women fit my mental model. This man did not.

It’s difficult to change ingrained ways of thinking, especially when they are not obvious to us. But one of the things that works is exposure therapy. If I see many pictures of Black men doing yoga, my mental model expands to include Black men in my universe of people who do yoga.

So, there’s that.

There’s also Terrence.

Terrence is one of the people who showed up in my ‘meditated with you—nearby’ circles one morning. If you click on the avatar, the image expands.

Photo used with permission

I’m guessing Terrence chose a photo of himself as a small boy because he wants to remind white people of something: that small boy is still inside that grown Black man.

Americans of northern European descent, in general, are not afraid of elementary school-aged Black boys. But we are, in general, afraid of young Black men.

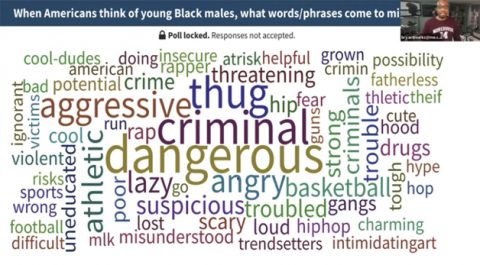

Rev. Dr. Bryant T. Marks is a tenured Professor of Psychology at Howard University and CEO of the National Training Institute on Race and Equity. In their training sessions across the country, participants are asked, “When Americans think of young Black males, what words/phrases come to mind?”

According to Dr. Marks, the consistent, dominant answers to this question are: Dangerous, Criminal, Thug, Rapper, Athlete.

Says Dr. Marks,

“Imagine walking through life with this as Your personal brand, that when people thought of you—yes, You—they literally thought this… You walk into the office building for the interview, this walks in with you. You walk into the bank for the loan, this walks in with you. You walk down a street past that police officer, this walks with you. You walk into the office hours of that professor seeking help, this walks in with you.”

We have been exposed to messaging to see people in a certain way and we can be exposed to messaging to see people differently.

We can learn.

I can learn.

Chewing the Cud of Good

Thankful for the anticipation of spending a Friday evening outdoor dining with friends.