My great-grandfather, Emil F. Folda, was born in 1866 in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and was brought to a sod house near Heun, Nebraska, as a toddler. The family relocated to take advantage of the Homestead Act and soil with fewer rocks. His mother died when he was 12; at 21 Emil was happy to leave the farm to work for his uncle.

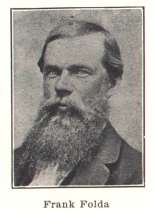

Uncle Frank ran a general store in Schuyler, Nebraska, and as he became wealthy, he founded banks. I don’t know if he was an honest merchant or if he cheated.

According to records, Frank Folda’s facility with Czech and English enabled him to provide helpful assistance to new immigrants from čechy. Was he a reliable translator? Or did he use his language skills to benefit himself?

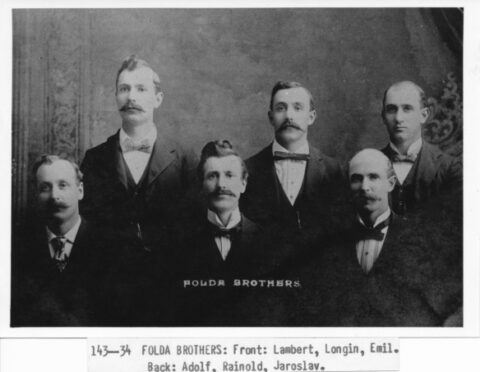

Frank’s nephew Emil Folda was one of seven brothers: Lambert, Longin, Emil, Adolph, Rainold, Jaroslav, and John, and three sisters, who are mostly unmentioned.

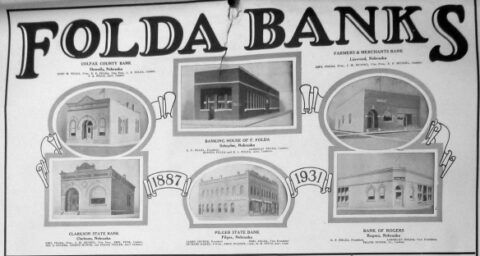

Uncle Frank brought the seven Folda brothers (not the sisters) into banking. They worked in the six Folda banks in six small Nebraska towns: Schuyler, Clarkson, Howells, Pilger, Rogers, and Linwood.

At the time of Frank Folda’s death in 1892, he owned over 4,000 acres of land west of Schuyler, 600 head of cattle, 50 horses, and an island in the gulf of Green Bay, Wisconsin. Is it possible for an honest merchant, an honest banker, to acquire such wealth?

Emil Folda became the President of four of the Folda banks. Essentially, he was the Jeff Bezos of the Clarkson-Schuyler area, and I believe he enjoyed his status at the top of the pyramid. Granted, it was a small pyramid, but if it’s the only one around, well then, you’re still at the top.

In the 1920s, banks in the Midwest began to fail. According to ClarksonHistory.wordpress.com:

Crop prices, that had been high during WWI, plunged beginning in 1920, and after a brief uptick from 1923-25, continued downward until 1932. Farm income, which had averaged $1,610 per year during WWI, dropped to $245 per year during the 1920s (Olson 1966). The value of all farm property in Nebraska dropped 33% from 1920 to 1930, and the value of land and buildings decreased more than 48 percent. Farmers who had taken on large debts during the war in order to buy land and increase production were finding it increasingly difficult to pay off their loans. Farms began to fail, followed by the small town banks that financed them.

Did Emil Folda make bad loans, hoping for repossession? Did he plan to buy repossessed land for pennies on the dollar? Or did he try to do everything he could to help the farmers, but faced an insurmountable obstacle called the Dust Bowl?

In February 1933, there was a month-long run on United States banks. On March 6, the newly inaugurated Franklin Delano Roosevelt shut down the banking system for an entire week, to stem bank failures.

The Federal Reserve decided to reopen banks in stages, according to classification. Class A banks were solvent institutions in little or no danger of failing. Class B banks were endangered, weakened, or insolvent institutions that were thought to reopen after an indefinite period of reorganization. Class C banks were insolvent institutions that would not be allowed to reopen. By March 15, banks controlling ninety percent of the country’s banking resources were open, but 4,000 banks would remain closed forever.(Annual Report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1934)

At the time, five of the Folda banks were run by Foldas, four of them with my great-grandfather as President. Joe Mundil, an immigrant the Foldas looked down on, ran the sixth bank, in Linwood.

The Linwood bank was declared sound and was allowed to reopen.

At the end of 1933, the five Folda banks were permanently closed.

In 1935, Emil Folda, the first person to own a motorcar in Clarkson, Nebraska, sat in his car in his garage with the garage door closed. He turned on the engine.

His son-in-law, my grandfather, was summoned to his bed, where the great man lay. The doctor informed my grandfather that Emil Folda had died of a heart attack. My grandfather was a man of few words and used none to tell the doctor he did not believe him.

If someone completes suicide, does it help or hurt the family to pretend the cause of death was something else?

If someone knows they have—via sins of omission or commission—caused others to lose their money, their homes, their farms, does that cause the offspring to have a strange or estranged relationship with money?

It doesn’t matter where my odd feelings about money came from. What matters is what I do with them, and what I do.

Chewing the Cud of Good

Thankful for Byron Katie who said, “Who would I be without this story of what I cannot know to be true?”

“Every generation blames the one before.” It’s from a Michael MacDonald (?) song from about 1990. I broke down sobbing in my car when I heard it while sitting in the parking lot of the hospital where my mom was dying. It was the slap in the face I needed to stop blaming my relatives, even ones I never knew, for anything and everything I could pin on them. I never got the chance to apologize to my mother.

Chris, I know the song. Thank you for the reminder, not of the song, but of my own responsibility for my life, and for the need to say things while we still can. In case it helps, I do believe that if we want someone to hear us and they want to hear us, it’s possible to say something they can hear, even if they’re not on the planet anymore.

Mike + The Mechanics, The Living Years