I grew up in New Jersey, spent a decade in Minneapolis, then most of my life in and around Chicago. Work moved me to Cincinnati and when I didn’t need to be here for work anymore, I surprised myself and stayed.

If you want to understand a place, it helps to know a bit about the history. This is a bit about Cincinnati, written in June 2019.

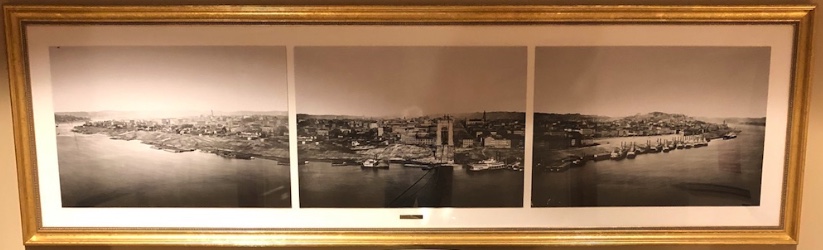

There is a photograph from 1860 that hangs in the elevator lobby of my condo building. Most people who look at it, if they look at it at all, probably think “That’s pretty,” or “What an interesting historical photograph.”

I don’t see a pretty picture. I see a warning.

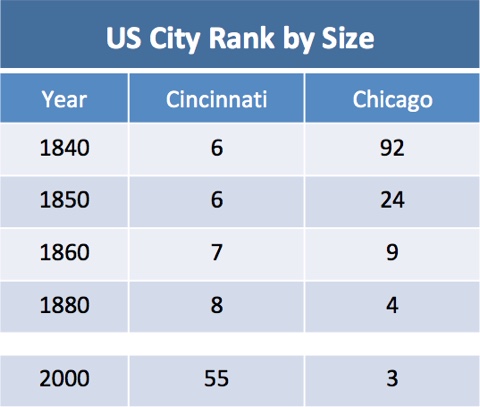

The warning is easy to miss. The construction of the John A. Roebling Bridge, the model for the Brooklyn Bridge, commands the center. Construction began in 1856, when Cincinnati was the sixth largest city in the United States, bigger than Chicago.*

Beginning in the 1820s, if you were in the east and wanted to travel west, you traveled by water, by steamboat. Cincinnati was a port city and like all port cities when the flow of goods and people was high, it boomed.

If you asked Cincinnatians walking along the street in 1860 how long they thought the current boom would last, they probably would have looked at the bridge and the buildings and homes under construction and guessed several years, maybe decades, maybe more. Few probably would have given the correct answer: “It’s already over.”

The ending of the boom in Cincinnati began on January 24, 1853, when the railroad route between New York and Chicago was completed. People who had traveled by boat instead traveled by rail. And they did not travel through Cincinnati.

The Roebling Bridge would be completed in 1866, but the steamboats, on the right side of the photo, are already idle.

When I was in my 40s, on a work trip in London, I picked up a copy of Charles Handy’s The Empty Raincoat. I believe the US version is called The Age of Paradox. In a chapter called “The Road to Davey’s Bar,” Handy writes about the sigmoid curve.

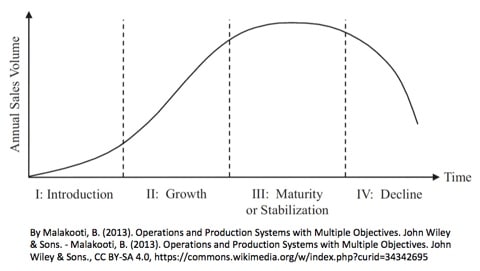

Handy had been looking for the turn for the road to the bar and couldn’t find it. He asked a passerby who told him to “go down the road a ways and then look back, you’ll see it.” Handy’s point was that some things are easier to see in hindsight. He points out that we live on the sigmoid curve—things begin, they develop and grow, they peak, they decline, they end. This is true of a product, a project, a career, a life.

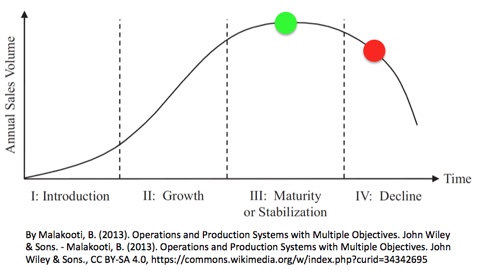

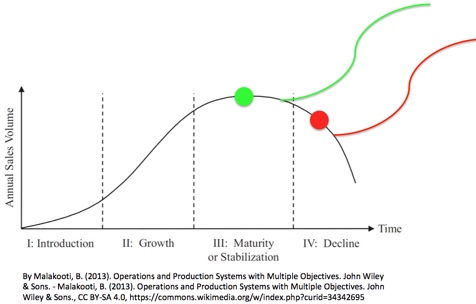

Handy believed a good business, and a good life, is made of a series of successful leaps to a next curve. The goal is to innovate before decline sets in, while we still have the energy and resources to make the change. But the challenge is that it’s hard to see we are already at the peak when we are at the peak. Handy says we should always assume we are farther along the curve than we think, closer to the red dot than the green.

The longer we wait, the less able we are to change, to start a new sigmoid curve.

When I was in my 30s, I planned to retire at 62. In my 50s, I revised that to 65—I was attempting to stretch the curve, which makes sense—when you are riding a successful curve it feels good. But at 61, it became apparent that it was time for me to make a change. I left my job at 62, not 65. It was later than I thought.

I might have done some things differently at 60 if I had known I was leaving full-time work in two years instead of five. Maybe not, but I know I would have done some things sooner than I did.

Now I tell myself that I have twenty years on this next curve of being a writer, that it is equal to the time between being an intern at Arthur Andersen to starting my business as a freelance consultant.

But maybe I don’t have twenty years of being an author. It’s probably later than I think. I need to see reality. I need to read the signs. Even in my 60s, I need to be agile.

* Footnote, US census data:

Chewing the Cud of Good

These penguins sit on my nightstand and make me happy. I made the short speckled one in second grade. The beige glaze’s transformation into aqua sprinkles astonished me. The copper one is from my friend Andrea. They remind me of my high school friend Steven, who liked Monty Python. “What’s on the telly-vision then?” “Looks like a penguin.”